When Google makes a change, there tends to be a period of panic and anger—and the recent changes to match types were no exception. The internet threw up its arms in justified frustration—account structures and workflows honed over the years just got hosed down by “close variants.”

In my view, single keyword ad groups, or SKAGs, were the most affected. SKAGs thrive on high levels of control over keyword syntax, yielding perfect keyword to ad to landing page relevancy.

There is no “right” way to run an account, and there’s an argument to be made for every paid media perspective. However, when Google changes the rules of engagement, some strategies have to be retired.

It’s time to say goodbye to SKAGs as we’ve known them, and embrace single theme ad groups, or STAGs.

New campaign structure, same concentrated strategy.

But before we say goodbye, it’s important to understand why the strategy was so successful for some and how to carry that value into the new “intent” era.

What are SKAGs? Why did SKAGs work?

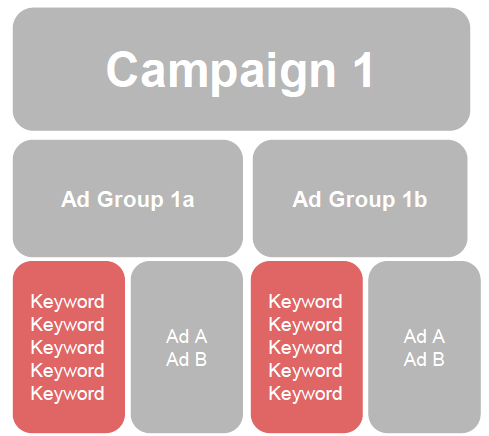

Single keyword ad groups are exactly what they sound like: one keyword per ad group (sometimes on multiple match types).

SKAG account structure follows one of the following formats:

- Single ad group per campaign with a micro-budget or shared budgets.

- All ad groups in one campaign with a giant budget.

- Varied numbers of ad groups (sometimes healthy, sometimes not) per campaign with budgets strategically set in relation to the products or services represented.

Traditionally, keywords like “trainer” and “training” would have their own ad group, and negatives would be used to direct traffic. This strategy would allow advertisers to craft ad copy that specifically leveraged language in the ad group and landing page.

In theory, advertisers could improve their quality score, get cheaper clicks, and feel in control of their budget.

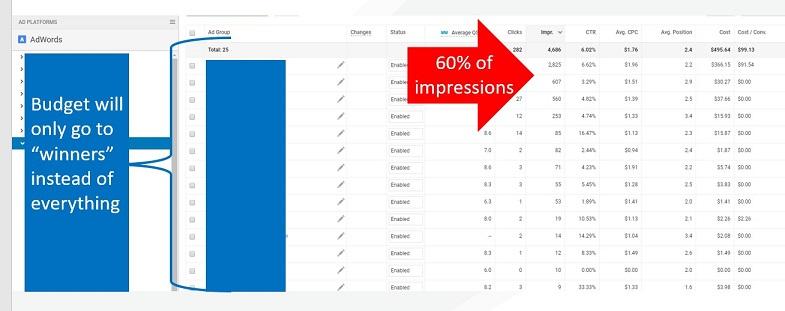

In actuality, what would often happen is these structures would concentrate budget in a few select ad groups/keywords—depriving important parts of the business.

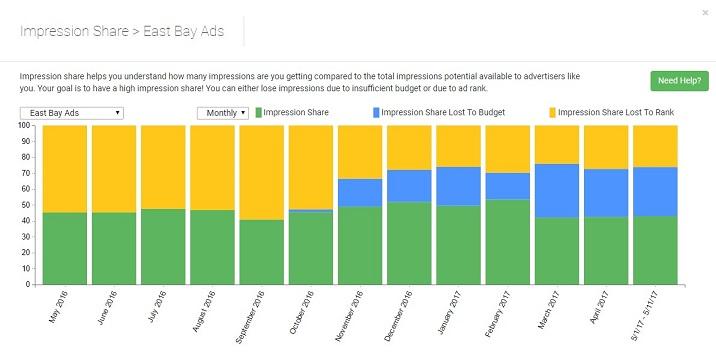

Impression share lost due to rank and budget.

By design, SKAGs need to put all ad groups in the same campaign or have micro-budgets. Advertisers who opt for micro-budgets are susceptible to impression-share loss. Dumping all ad groups in the same campaign (or exceeding the healthy ad group ratio of five to seven) is a recipe for budget misallocation.

It’s worth noting that dynamic keyword insertion (DKI) often found a home in SKAG accounts because of the focus on keyword to ad to landing page relevance.

The slow death of SKAGs

When the first round of close variants hit, misspellings, abbreviations, and varying suffixes—like “ing” “er” “ed”—of keywords began to lose credit for their traffic. Google is predisposed to favor keywords/ads with data, so lower searched terms would struggle to get a shot, while highly searched variants would own budgets (even if they were less predisposed to profit).

Then, exact match evolved—order no longer mattered and implied words were allowed:

“Lawyer” matches to “attorney”; “mowing lawn” matches to “cutting grass.” And mass panic ensues.

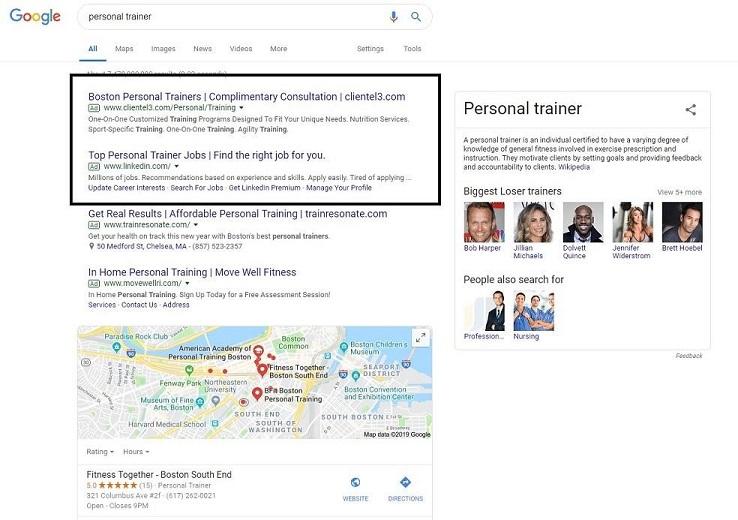

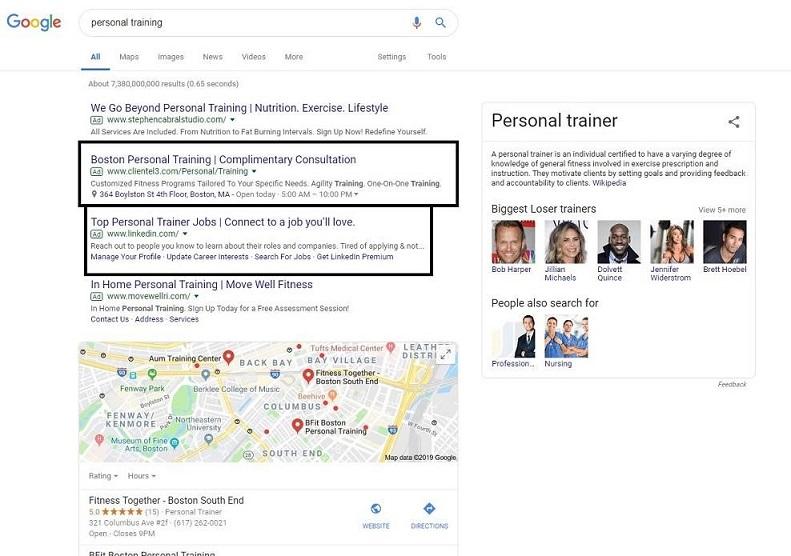

SERP for “trainer” search.

SERP for “training” search.

Historically, advertisers bid more aggressively on exact match because it meant you had the most protections against wanton matching. Now, “exact” might as well be “broad.”

SKAG accounts had one last hope: phrase match. Up until the change, phrase match locked in the order of keywords and didn’t allow for implied words to take the chosen word’s place.

For all the value they brought, there are three really important reasons SKAGs no longer hold their own against other PPC strategies:

- Campaign limits on negatives: A search campaign can “only” have 10,000 negatives. Because negatives don’t allow for close variants, but active keywords do, it will be impossible to fully protect a given ad group or campaign from all the negatives needed to protect against waste and direct traffic.

- Budget constraints: If a keyword has an auction price (top of page/average CPC) that exceeds 10% of the campaign daily budget, it makes it challenging to secure value out of the campaign. Over split campaigns won’t have enough fuel for their keywords, and giant campaigns tend to have budget allocation issues. This means important parts of the business starve while high-volume keywords get all the budget.

- Time investment: Healthy ad groups will have three ads per ad group, and the ability to create three unique/interesting ads for SKAGs presents a true challenge for even the most prolific copywriters.

There is one use case of SKAGs I heartily support and hope continues on: a single long-tail broad keyword with every other keyword added as an exact match negative.

This strategy allows you to gather data on how your prospects may be searching—and at what auction price you can secure them.

STAGs are here to save the day!

STAGs: The new solution

Single theme ad groups focus on themes rather than syntax, ensuring there are three to five similar themed keyword concepts per ad group.

STAG account structure will follow one of the following formats:

- Service/product category as the campaign: Audience/messaging governing the ad groups.

- Location/market as the campaign: Products/services as the ad groups.

- Profit probability as the campaign: Corresponding products/services as the ad groups.

The benefit of running a STAG structure is in the ability to set budgets aligned with profit as opposed to PPC mechanics. No more budgeting for every variant under the sun—you can now play favorites and direct budget where it will do the most good.

While it’s true this structure misses out on perfect keyword to ad to landing page relevancy, it more than makes up for it in the metrics that matter: ROAS, impression share, and conversion rate.

An easy way to make close variants an innovative “hack” as opposed to a frustrating thwarter of structure is to bid on the mistake. For example, the word “oxygen concentrator” usually goes for $7-$8 per click, but by bidding on the variant (in this case, the misspelling), we’re able to secure $4-$5 average CPCs. At scale, this means we can usually fit at least one extra click per day, increasing the odds that our conversion rate will secure us a lead.

Audiences have all but killed the need for perfect keyword matching because they allow you to prequalify traffic before you invest in them.

Layering in-market and custom affinity audiences on search campaigns ensures the budget is going where it can do the most good (and protecting against dubious intent).

For example, bidding on the keyword “moving services” can apply to a local mover who will help a renter move to a new apartment, just as much as it can apply to a several hundred thousand dollar deal to relocate an office. With audiences, you can exclude the intent that isn’t a good fit (and driving up your costs/giving you false positives on cost effectiveness).

How to migrate from SKAG to STAG

We’re ready to embrace the new way! Huzzah STAGs! Now, time to restructure your account to reflect this change.

Restructures always come with some risk for disruption to lead volume and short term performance fluctuations, but there are ways to mitigate them. Here are three rules to follow to make your restructuring from SKAG to STAG simple.

Rule #1: If you trust your conversions, don’t move them

Restructures almost always mean initiating learning periods and fluctuation in performance. The biggest culprit is often pausing a converting keyword.

Working through a restructure means creating a lot of net new entities—even if the long term will benefit, you still need to protect your short-term KPIs. As a rule, the keyword/ad group/campaign with conversions should get to stay put.

For example, in the below example, we would work on moving “rigging,” “rigger,” and “rig” keyword concepts into the “NJ Rigging” ad group.

A big reason for this is you want some stability built into the restructure as opposed to having a complete rebuild.

If you’re faced with multiple keywords/ad groups with good conversion data, then allow auction price to be your guide.

In the above example, we see that the average CPC for “rigging” concepts is cheaper than “mover” concepts, so there’s a priority on moving those first because mistakes aren’t as costly.

Rule #2: Not everything will make the cut

It can be hard to break up with a keyword, but sometimes for the good of the account, sacrifices have to be made. If a keyword is just a variant of another keyword, it likely needs to be paused. Additionally, there may be keyword concepts that just don’t fit the budget. Use this time to take stock of keywords that are truly important versus could be covered by others or highlighted in extensions.

Rule #3: Pause so you can try again

One of the classic blunders in PPC is changing an ad or keyword as opposed to duplicating them and changing the duplicate. The moment you make a change, the entity is gone, and you need to deal with the ramp up period for a net new entity without the safety net of going back to your original entity.

It’s also important that you give your new structure the time it needs to prove itself (and that you embark on this restructuring journey at a time when you can handle some flux).

Time to embrace STAGs

Abandoning a workflow or process can be scary—humans are incredibly habitual creatures. Yet the data paints an optimistic picture: We will be able to free ourselves of granular mechanics in favor of strategic pragmatism.

Managing an account will now be about what it should always be about: data-driven lead generation governed by profit centers and priority markets. If a campaign is built, it’s built because it directly ties into a business need, as opposed to attempting to game PPC mechanics. This shift is a good thing, and you should embrace STAGs to make the most of it.

Comments

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.