At some point during May 2017, the security systems of American credit monitoring agency Equifax were compromised.

The names, addresses, Social Security numbers, and in some cases credit card details of approximately 143 million Americans were accessed during the attack — almost half the American population. News reports would later reveal that the perpetrators of the attack managed to gain access to Equifax’s systems by exploiting a vulnerability that had in fact been identified in March, a flaw that Equifax could have easily secured.

The true extent of the damage has yet to be fully determined as of this writing, and according to credit monitoring expert and former Equifax employee John Ulzheimer, “there may never be a way to know.”

At this point, it’s unclear whether Equifax will face any significant consequences for its utter failure to protect the digital identities of half the American population. (To add insult to injury, it appears that not only did Equifax wait six weeks to report the breach, but that it further delayed informing the public until it had successfully acquired an identity protection firm so it could later profit from the breach.)

Had this situation unfolded in Europe, things would likely be very different.

Europeans (and the European Union in particular) care a great deal about online privacy and data protection. From “controversial” laws that protect Europeans’ “right to be forgotten” to wider cultural attitudes about consumer protections, it’s much easier — and safer — to be a consumer in Europe than it is in the U.S. For American companies marketing to European consumers, however, life could soon become a lot more difficult thanks to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR (PDF of full text).

In this post, we’ll be taking an in-depth look at the GDPR and how it could affect your business. We’ll be answering common questions about this unique legislation, as well as identifying potential pitfalls to avoid and urgent actions you should consider taking before the rules go into effect.

For the sake of simplicity, most of the points below are framed within the context of what the changes will mean for American, Canadian, and British companies (as that’s where the vast majority of our readers are), but the General Data Protection Regulation will apply equally to all businesses that market to or do business with European Union member states, regardless of where in the world that business is located.

1. What is the General Data Protection Regulation?

The GDPR is a package of new legislative rules being introduced by the European Union to make it easier for residents of EU countries to protect their personal data online. The regulation was officially approved on April 27, 2016, and will formally go into effect across the entirety of the EU by May 25, 2018.

Unlike EU directives, which require further action on behalf of member nations’ governments in order to enact, the GDPR is (as its name states) a regulation, meaning that the rules will immediately become legally binding on May 25, 2018, with no further action or measures required from EU member states.

2. What Data is Covered by the General Data Protection Regulation?

Virtually all data pertaining to individuals residing in the European Union will be protected by the GDPR. This includes not only uniquely identifying information such as official identity documents similar to Social Security numbers in the U.S. and Social Insurance Numbers in Canada, but also information routinely requested by websites, including IP and email addresses, physical device information such as a computer’s MAC address, individuals’ home addresses, dates of birth, and online financial information including online transaction histories.

Image via Council of the European Union

However, that’s not all the GDPR is intended to safeguard. The legislation also protects user-generated data such as social media posts (including individual tweets and Facebook updates), as well as personal images uploaded to any website, including those that do not feature the likeness of the person who uploaded the image. The GDPR also covers medical records and other uniquely personal information commonly transmitted online.

Essentially, the GDPR protects any and all personal user data across virtually every conceivable online platform.

3. Why is the General Data Protection Regulation Necessary?

Many European countries already have their own robust data collection and storage laws, but the GDPR’s purpose is to make safeguarding users’ data stronger, easier, and more uniform across the European Union, unifying existing data protection regulations across its 28 member states.

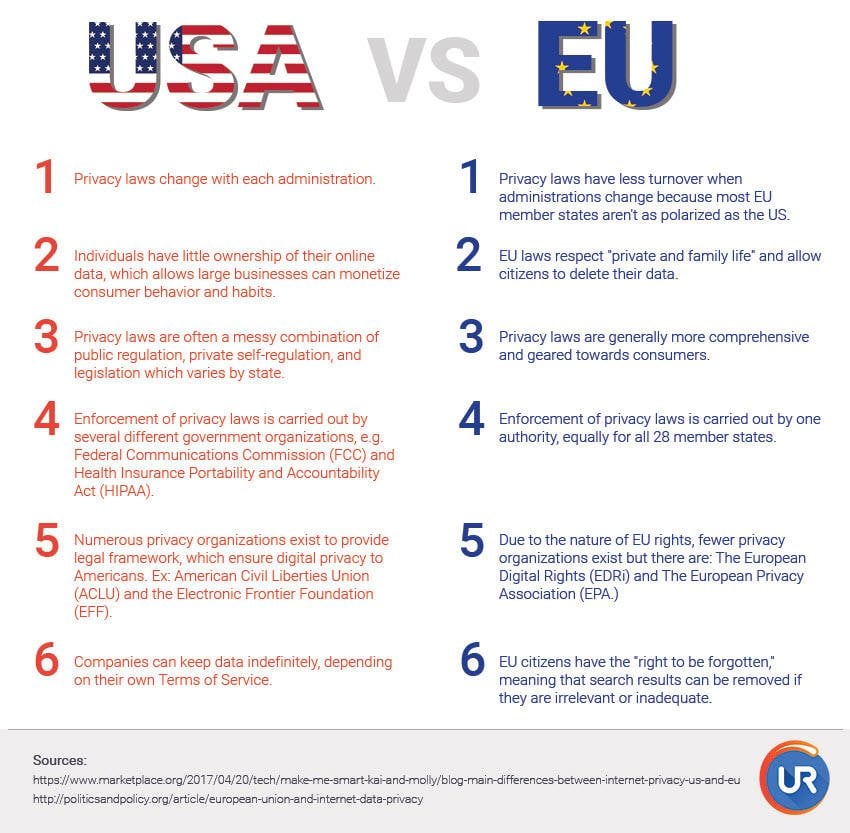

Image via UR

This makes it easier for European consumers to take a more proactive role in how data about themselves is shared and retained by private enterprises, and also offers businesses overseas a single regulatory framework to which they must adhere, rather than the patchwork of various laws and protections currently in law across the EU. This could be a considerable benefit to companies that market to several EU member states, as the GDPR will supersede any and all existing data privacy and protection laws currently upheld by the EU’s member states.

4. What Does the GDPR Mean for Overseas Businesses?

The GDPR means that companies all over the world, irrespective of where they are based, will have to comply with the legislation’s laws on how user data about EU nationals is processed, gathered, and stored.

Compliance with the GDPR means companies essentially have to switch from an “opt-out” approach to an “opt-in” approach; rather than forcing users to opt out of having their personal data collected and stored, users must instead give companies their express permission with regard to virtually all aspects of an individual’s data security. This applies to everything from something as seemingly innocuous as automatically signing up users to an email newsletter to more wide-scale efforts, such as the pseudonymization of user data.

One of the more contentious elements of the GDPR is a section of the legislative package known as Article 22, which concerns algorithms and automated user profiling. Under the GDPR, European users have the legal right to question or appeal how their personal information is presented by algorithms such as those used by Google in its search business. This is an extension of the “right to be forgotten” laws that made headlines when the measures were first introduced in the EU and Argentina back in 2006.

Several legal experts and scholars have taken exception to the current phrasing and legal grounding of Article 22, but even if the current language is revised to be less legally ambiguous, we can realistically expect there to be some element of legislative oversight when it comes to algorithmically generated data.

What Effect Will Brexit Have on GDPR Compliance?

Great Britain’s forthcoming exit from the European Union will have absolutely no impact on the EU’s expectations for GDPR compliance whatsoever. Ironically, had Britain decided to remain in the EU, British consumers could have also looked forward to enjoying the kinds of robust protections offered by the GDPR alongside their counterparts on the Continent, instead of dealing with what could accurately be described as one of the most Orwellian domestic surveillance programs in the world.

Regardless of what Britain decides to do with its own privacy and data protection laws (such as they are), British companies will have to adhere to the exact same rules and regulations as companies located anywhere in the world. Given the utter chaos that has largely defined Britain’s Brexit “strategy,” which some might say is an extraordinarily generous term for what’s actually happening, it’s unlikely that GDPR compliance clauses will be negotiated as part of broader exit terms.

One thing that is practically guaranteed, however, is that British companies cannot (or should not) expect special treatment when it comes to the GDPR, and as such should prepare accordingly.

5. Do I Need to Hire a Data Protection Officer to Comply with the GDPR?

You may have a legal obligation to hire a Data Protection Officer (DPO) to ensure compliance with the GDPR. However, there are exceptions. You only have to hire a DPO if:

- Your organization is a public authority (i.e. a company that exercises control over the maintenance of public infrastructure or has broad powers to regulate public property)

- Your organization is engaged in large-scale systematic monitoring of user data

- Your organization processes large volumes of personal user data

Unfortunately, the official text of the GDPR as it stands today is unclear regarding the definition of “large-scale” data processing. However, there is some guidance, albeit somewhat limited in its scope.

Many of the provisions of the GDPR legislative package could not be agreed upon immediately. Some of these clauses were deferred to the GDPR’s Recitals, which are legal texts that establish the reasoning behind certain acts within an item of legislation. One such recital — Recital 91 — states that, “The processing of personal data should not be considered to be on a large scale if the processing concerns personal data from patients or clients by an individual physician, other health care professional or lawyer.”

So what can we infer from the maddeningly ambiguous Recital 91? Basically, if the data processing your company engages in as part of its day-to-day operations is beyond the realistically manageable workload of two professionals, it could be argued that this data processing is “large scale.” Unfortunately, as with much of the GDPR, context is crucial in determining whether a company is in compliance or not. If in doubt, it may be worth considering hiring a dedicated Data Protection Officer.

Cloud-Based Storage is NOT Exempt from the GDPR

While we’re on the topic of whether you need to hire a Data Protection Officer to comply with the GDPR, it’s worth mentioning that companies that rely upon cloud-based storage providers will not be exempt from the GDPR. This means that if your company uses Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, or Microsoft Azure, you will NOT be able to blame Amazon, Google, or Microsoft for failure to comply with the GDPR.

6. What Happens to Companies That Fail to Comply with the GDPR?

Failure to comply with the GDPR carries heavy penalties.

The first step of the process is a formal written warning, which can be issued to a company even in cases of unwitting violations; ignorance of the law is not a valid excuse for breaking it. The next stage of punitive actions can force companies in violation of the GDPR to undergo regular periodic data integrity audits to ensure compliance, which also means surrendering access to potentially sensitive, confidential, or proprietary information to an auditor.

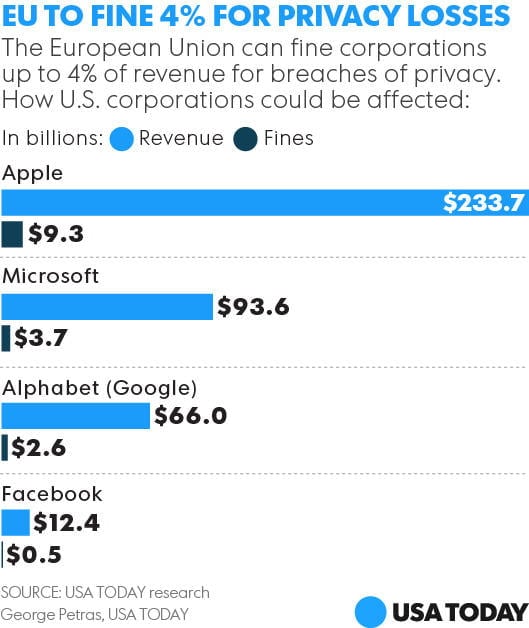

For companies that still haven’t taken the hint, firms that are found to have breached or violated any part of the legislative package after initial sanctions can be fined up to €20 million (approximately $23.5 million USD) or 4% of a company’s worldwide turnover, whichever is greater.

Image via USA Today

7. What Does the EU Expect from Overseas Companies Regarding Compliance with the GDPR?

It will be the responsibility of a company’s Data Protection Officers or data controllers to ensure that European users’ data is being sufficiently protected and/or anonymized, and it will be the data controllers who will be among the first to be held to account if breaches or violations are reported.

Under the GDPR, data controllers will be expected to report any and all possible data breaches to the relevant EU authorities within 72 hours of detection. Furthermore, users affected by data breaches must also be notified by a company’s data controllers, with the exception of compromised pseudonymized data, which is not subject to the same reporting requirements as non-anonymized data.

Something else companies dealing with the GDPR will have to reckon with is storing records of user consent. Although it’s difficult to say with any certainty, I’d wager most companies keep minimal (if any) records concerning users’ consent to have their data stored or processed, but this will be an expectation — and legal requirement — under the GDPR. Companies must be able to prove that a specific user not only gave their initial express consent to have their data stored, but also that the user’s consent records are accurate and up to date.

8. What Counts as ‘Pseudonymized Data’ Under the GDPR?

I’ve mentioned “pseudonymized data” several times, but what exactly is pseudonymous data?

Image via Tom “Marketoonist” Fishburne

According to Recital 26 of the GDPR, pseudonymized data is “data rendered anonymous in such a way that the data subject is not or no longer identifiable.” Essentially, this means that any and all identifying information regarding an individual user must be removed entirely from all stored or processed data so that the identity of a specific user cannot be revealed — even to the company or authority responsible for anonymizing the data itself.

Remember earlier when we went over the kinds of identifying information protected by the GDPR? Well, it doesn’t end with dates of birth, Social Security numbers, or financial information. The GDPR also protects information such as a person’s religious, philosophical, or political beliefs, information about their sexuality or sexual orientation, records of membership to organizations such as labor unions, and genetic or biometric data including fingerprints and DNA. Since all this data is protected by the GDPR, the measures a company takes to pseudonymize its data must ensure these data points are also removed completely.

The primary reason that the text and Recitals of the GDPR uses the term “pseudonymized data” rather than “anonymized data” is largely one of pragmatism. It’s very difficult to completely remove all identifying information about a user. Truly anonymized data falls outside the jurisdiction of the GDPR, but given that it’s highly unlikely many data controllers would either be able or willing to truly and completely anonymize their users’ data, the GDPR uses the definition of pseudonymous data instead.

It’s also worth noting that, according to one particularly well-cited study, approximately 87% of American adults could be accurately and uniquely identified using just three data points — date of birth, gender, and a five-digit zip code — using publicly available census data, a sobering statistic that highlights why such robust pseudonymization measures are needed, particularly in light of large-scale data breaches such as the Equifax security incident.

9. What is ‘Affirmative Consent’ in the Context of the GDPR?

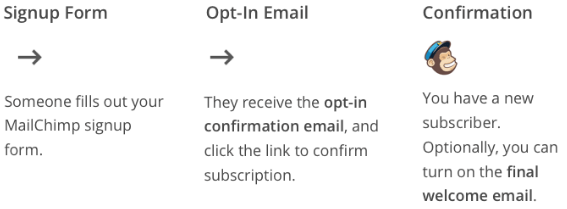

Many marketers will already be familiar with the concept of affirmative consent, a principle that states individuals must, for example, give their express permission to a company before it can add that person to a mailing list. This is the “opt-in” approach.

Image via Mailchimp

Under the GDPR, affirmative consent laws will be strengthened. This means that companies that conduct business with EU nationals will no longer be able to bury hidden clauses in lengthy, verbose terms of service agreements or otherwise obscure their intentions through legal trickery. The GDPR states that EU nationals must not only give their express permission before a company can process or store their data, but also that companies must provide EU nationals with clear, easily understood opt-in processes that expressly state how users’ data will be stored, processed, or used.

What About Affirmative Consent for Minors?

Many companies deal with minors during the course of their business operations. App developers, entertainment websites, and other kinds of businesses routinely handle data pertaining to minors, and the GDPR has specific guidelines on how this data should be handled.

Affirmative parental consent is vital to collecting, storing, or processing the personal data of EU nationals under the age of 13. Data controllers must be able to demonstrate that affirmative parental consent was granted upon request, and it’s important to note that this consent can be withdrawn at any time – as is the case with consent to permit adults’ personal information to be processed.

10. How Stringently Will the GDPR Be Enforced?

“I only have a handful of email newsletter subscribers in Europe,” I can hear you say. “Surely I don’t need to worry about all this for just a handful of users?”

Wrong.

When the GDPR goes into effect in 2018, it will become one of the most robust consumer data protection initiatives in the world – if not the most. As a result, companies should expect the regulation to be rigidly enforced.

Although you may not be legally required to hire a dedicated Data Protection Officer, you absolutely MUST comply with the GDPR regulation if you collect, store, or process data from ANY EU nationals, regardless of how many. Failure to do so may result in the kind of stunning financial penalties I detailed earlier.

User Rights > User Experience

The GDPR promises to be one of the most far-reaching and ambitious consumer protection programs ever devised. However, although the implementation of the GDPR is likely to cause some businesses more difficulty than others (such as enterprise firms that offer “big data” products), it’s important to remember that this legislation is being introduced to protect users’ rights in a time at which almost every conceivable aspect of our lives is stored online – and is highly vulnerable to exposure and exploitation.

Just as there was when Canada implemented its CASL legislation, there has already been a great deal of hand-wringing about the new regulation, as well as the predictably vocal opposition from many American businesses that see consumer protections as little more than inconvenient obstacles to even greater profits.

To me, the real question isn’t whether the GDPR will be good or bad for American businesses, but rather why the U.S. isn’t developing robust consumer protection laws of its own. As one of the 143 million people who were affected by the recent – and completely preventable – Equifax breach, I know I’d love to see legislation like this passed (or even discussed) in the States. How about you?

The Ultimate Guide to the GDPR for Advertisers

If you want even more tips on…

- What the GDPR is

- How Google AdWords will be impacted by the GDPR

- How Facebook will be impacted by the GDPR

- How to acquire consent from paid traffic

![Search Advertising Benchmarks for Your Industry [Report]](https://www.wordstream.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/RecRead-Guide-Google-Benchmarks.webp)