I’ve been an editor for many years (don’t make me admit how many) and a writer for even longer. After even a few years in the game, every editor develops their own list of bugbears (translation: pet peeves) – the mistakes or missteps that really stick in one’s craw (translation: annoy the pants off one).

I work with many different writers, and since I share these tips privately all the time, I figured it was time to pull them from the shadows of Track Changes comments and make them a matter of public record.

Most of the people who read this blog are marketers and business owners, so I’ve written this post with you in mind. These self-editing tips will be particularly helpful for copywriters doing business writing (i.e. writing for corporate blogs and websites, lead generation magnets like white papers, etc.) – but truly, this advice can improve almost any type of writing.

So if you’re looking to up your writing game and get better at self-editing, read on. I’ll start with some common style problems I run into again and again.

7 Lazy Writing Crutches & Bad Habits to Avoid

Inexperienced writers often make the mistake of thinking that “good writing” is fancy writing. They mistake clarity for dullness. If this is your attitude, what you usually end up with is overwriting. It can come off as show-offy, and it’s uncomfortable to read.

These seven bad habits muck up your writing, slow your reader down, and obscure what you’re trying to communicate. Relentlessly search these out and destroy them in your content editing phase.

The so-called elegant variation

“The elegant variation” is an old term (coined by usage expert Henry Watson Fowler) that refers to an overuse of rare or poetic synonyms for more common words. The term is meant to be ironic – the effect is not actually elegant. Instead, elegant variations usually feel overwrought (or as the kids say, “try-hard”).

Coco Chanel said that – but she didn’t refuse to hobnob with Nazis

Here’s Fowler, in his Dictionary of Modern English Usage (first published in 1926):

It is the second-rate writers, those intent rather on expressing themselves prettily than on conveying their meaning clearly, & still more those whose notions of style are based on a few misleading rules of thumb, that are chiefly open to the allurements of elegant variation…. There are few literary faults so widely prevalent, & this book will not have been written in vain if the present article should heal any sufferer of his infirmity.

Ouch, Fowler.

The elegant variation is common in journalistic writing, where writers often try to avoid repeating a noun – so you’ll see Google referred to as “the search giant” on second mention. But it crops up all over the place – when people say an author “penned a volume” versus writing a book, say. It’s cute to a point, but really easy to overdo.

A related bad habit is “said-bookism,” when writers feel the need to avoid the word “said,” so people are always “exclaiming” and “proclaiming” and “retorting” instead. There actually was a “said book” at one point, a kind of thesaurus of terms for speaking that writers could use to vary their dialogue tags. But as it turns out, most of the time, plain old “said” works better, and the repetition calls less attention to itself than the endless variations do.

$10 words

Ten-dollar words, AKA SAT words, tend to go hand in hand with elegant-variationism.

Any excuse to look at Hamilton’s noble brow

These are fancy-sounding words that crop up on vocabulary tests and in spelling bees and are rarely uttered in everyday speech. Two of my particular least favorites are “plethora” and “myriad” (protip: if you ever apply for a job at WordStream, don’t use these in your cover letter).

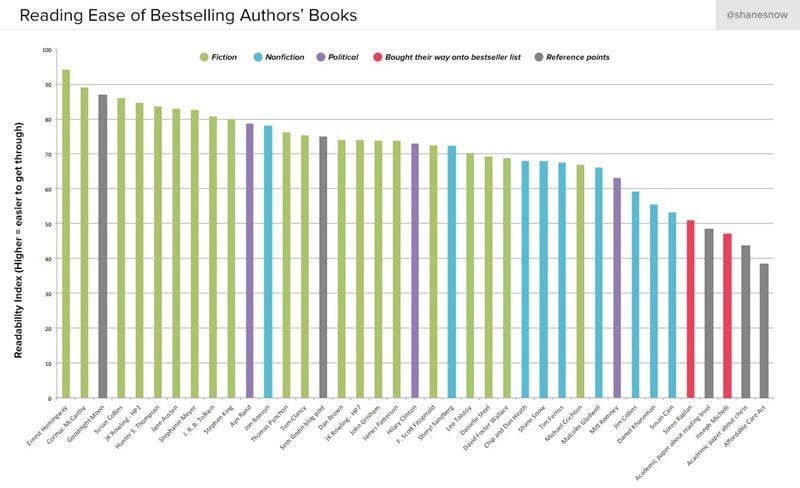

A lot of writers have a favorite go-to ten-dollar word. My husband loves “proleptic” for some reason. When self-editing, look for words that you tend to overuse, especially if they’re above a high-school reading level. (We found that top-performing ads, like most bestsellers, are written at a ninth-grade reading level!)

Latinate words

There’s nothing wrong with Latinate words and you can’t avoid them entirely – but there are a lot of cases where choosing Latinate words over Anglo-Saxon or Germanic words can make your writing sound academic or clinical and therefore less friendly.

Here are some examples of Latinate words vs. their Germanic counterparts:

But truly, you don’t need to worry too much about the etymological roots or origins or your words; just try to write in everyday speech. For example, I rarely hear people say “utilize” but I see it in writing all the time. “Use” and “utilize” both ultimately come from French but “use” sounds much more natural and friendly.

Commonly misused words

Words that are misused all the time always sound kind of wrong – even when used correctly!

For example, people are constantly writing “hone in on,” as in “hone in on the problem.” The correct expression is “home in on” – like a homing pigeon or homing device. A lot of editors will correct this use of “hone” (which means to sharpen, as in honing your skills or honing a knife) to “home,” but I prefer to just rephrase. After all, both “home in on” and “hone your skills” are clichés.

Other frequently misused words and terms include comprise, nonplussed, bemused, and beg the question. If you use them incorrectly, you’re going to tick off persnickety types, and if you use them correctly, all the people who don’t know what the word means are going to think you’re in the wrong. Accordingly I think it’s best to avoid them entirely.

Needless exaggeration

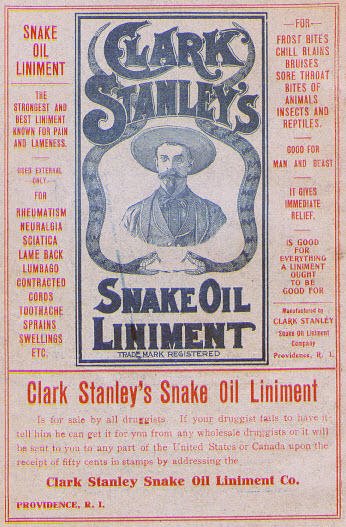

This tic is especially common in business and marketing writing, where writers naturally want to sell the value of whatever product or service they’re talking about, but you run the risk of sounding like a phony or a snake oil salesman.

“The strongest and best linament known for pain and lameness”

An example would be saying something “couldn’t be easier” instead of just saying that it’s easy. Theoretically, it could always be marginally easier…

Baseless assumptions & received wisdom

There’s a weird rumor that floats around the WordStream office – it’s that seltzer is bad for you. Specifically people seem to think bubbly water somehow leeches calcium from your bones (??). I don’t know where the myth came from, but there’s no evidence that it does this.

An example from the world of marketing is the received idea that consumers hate remarketing ads, so you need to set strict frequency caps on your retargeted ads. But we’ve found that conversion rates on remarketing ads actually increase with more exposure, not the other way around. It’s always good to question a “rule” and make sure it’s not just an old wives’ tale.

When reading over your writing, be on the lookout for claims that you can’t prove or back up with evidence. Just because you’ve heard something over and over doesn’t make it true.

Belabored metaphors

I don’t know any other way to say this: metaphors only make your writing better if they’re good. Clichéd metaphors add nothing (how many 80s rock songs use the simile “cuts like a knife”?). But even worse is the forced, overly belabored metaphor that doesn’t even really make sense. Like this example from a Harvard Business Review article called “The Dark Side of Efficient Markets”:

Those are indeed positive features. But every good thing is like a face caressed by the sun. The rays that light and warm the face automatically cast a dark shadow behind it.

Hmmm. Nope.

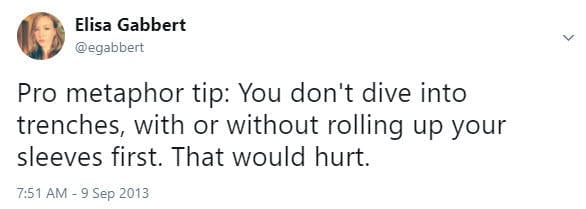

Related issue: the mixed metaphor, which is usually also a mixed cliché.

You can dive into a project or get experience in the trenches, but try not to do both at once. (What is it about trenches that confuses bad writers? Dan Brown once described a character as “learning the ropes in the trenches.”)

3 Ways to Make a First Draft Stronger

OK, we’ve talked about things to avoid and cut out of your writing. Now let’s talk about what you can add to make it better. First draft a little lackluster? Try one of these tactics when revising.

Add data, stats, authority

Remember when I said not to make baseless assertions? Here’s how you fix that – go looking for research and data to back them up. Stats are also great in an introduction to remind people why they should care about whatever you’re writing about.

For example, this post about how to write a welcome email begins with some stats on welcome email performance: Since they have on average 4x the open rate and 5x the click-through rate of a standard email marketing campaign, of course you want to get them right.

However, if you can’t find recent and authoritative research, skip it. And be wary of confirmation bias – the tendency to seek out sources that confirm what we already believe. It’s good to challenge your own assumptions, so if you find evidence that contradicts your argument, consider revising your argument.

Add INTERESTING details

Details add texture to your writing. But don’t let yourself off the hook too easy with boring, obvious details, or details that have no relevance to what’s happening.

The classic example of a lazy, pointless detail in fiction is “A dog barked in the distance.” A dog is always barking in the distance. Who cares? And sorry to drag Dan Brown again, but check out this passage from Angels and Demons:

Vittoria closed her eyes and breathed. Then she breathed again. And again. And again …

You don’t say.

Details matter in nonfiction too. For example, if you’re writing a profile of a woman, don’t describe what she’s wearing just because she’s a woman. We also don’t need to know what she ordered for lunch.

So how do you add interesting details? Work on your powers of observation. Look for what is unusual, then filter for what is relevant. That’s the Sherlock Holmes way: Notice first, then analyze. Holmes doesn’t tell people everything he notices, just the details that illuminate the case.

Teach people something

It seems so simple. The whole point of nonfiction is to teach people something, right? And yet – so much writing fails to do this, and therefore isn’t interesting.

If you want to be a great writer, make sure you are always learning yourself, so you have something to teach people. Read widely, try new things, and share what you learn. This can take the form of:

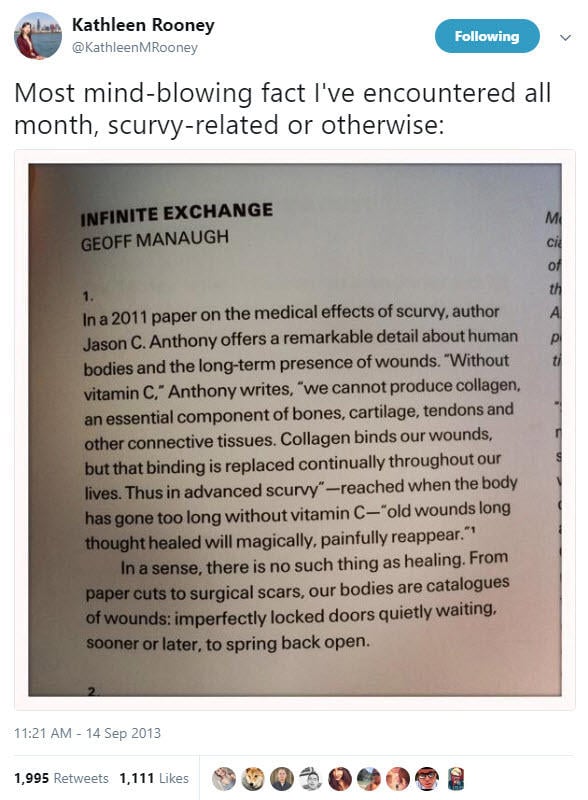

- Including interesting facts – I have an insatiable appetite for lists of mind-blowing facts. Start collecting fascinating knowledge and then you can drop it in as it comes up.

- Pointing people to more comprehensive resources – If you’re only able to touch on something that you have in-depth knowledge of, recommend your favorite articles, books, or films on the topic so people who are interested can learn more. (Want to get better at learning?! I love this book called How We Learn.)

- Sharing life wisdom – Obviously, you need to have some life wisdom before you can share it – but this doesn’t always come from age. I love when people teach me something only they could know. What have you learned from your unusual or difficult experiences? What’s it like to found a successful startup – and then watch it fail? What’s it like to play competitive Scrabble?

If you’re teaching people stuff, your writing becomes 10 times more interesting. Great ideas trump big words every time.