When Bill Clinton was campaigning for the presidency against George H. W. Bush in 1992, Clinton’s campaign strategist James Carville wrote three slogans on a whiteboard in the “war room” of their campaign headquarters in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Fear and Slogans on the Campaign Trail ‘92

The slogans were intended to keep Clinton’s campaign team focused on the most important issues of that election. A slight variation of the most famous of these phrases – “The economy, stupid” – became one of the most definitive political campaign slogans of modern times (and arguably helped Clinton win the presidency), and one that still resonates with voters and political hopefuls alike.

Now, you might be wondering what this has to do with marketing. Although marketers have a lot to think about, the wider economy often takes a backseat to more immediate concerns. However, understanding the principles of economics – and how people respond to them – is crucial for marketers in today’s highly competitive business environment.

Simply put, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

In his best-selling 1998 textbook, The Principles of Economics, Greg Mankiw identified 10 defining principles of modern economics. In today’s post, we’re going to look at some of these principles, the psychology behind them, and how you can leverage these principles in your marketing campaigns.

Principle 1: People Face Tradeoffs

Unless you studied economics in college, you might not be familiar with the term “opportunity cost.”

You probably have, however, heard the expression, “There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.” In case you were wondering, it is believed that the phrase originated during the late 19th century, when saloons would often offer patrons “free” lunches of salty food in order to entice people to buy drinks.

David Caruso tells it like it is.

Opportunity cost is the concept that, in order to acquire something we want, we usually have to give something up to get it.

For most marketers, the most common type of opportunity costs to overcome with their marketing plans are known as explicit costs; if you charge $250 for a year’s subscription to a software service, the prospect faces the explicit opportunity cost of being unable to purchase other goods or services with the $250 they spent subscribing to your software product.

Fortunately for marketers, this is one of the easiest economic principles to leverage.

It’s the Positioning, Stupid

Since the explicit opportunity costs of doing business are something that all consumers are aware of, leveraging this principle and overcoming potential hesitation is as simple as making the customer feel as though they’re getting the better deal. Note that I’m not advocating for intentionally misleading your prospects – far from it. I am, however, suggesting that your marketing messaging positions your product or service in such a way that the benefits of purchasing vastly outweigh the explicit opportunity cost.

As we’ve said plenty of times in the past, your prospects don’t want to buy things – they want to solve their problems. With this in mind, you need to make the benefits of purchasing your product or service so appealing that the prospect doesn’t even consider the opportunity costs inherent to their decision.

Case Study: Accounting Software

Let’s say you run a small business. You need to invest in some sort of bookkeeping software package, and you’ve narrowed it down to two choices: QuickBooks or Less Accounting.

In terms of price, the two platforms are similar. So how does Less Accounting – a much smaller company than Intuit – compete? By focusing on the benefits of its software and appealing to their ideal prospects’ desire to solve a problem, namely making bookkeeping less hassle (clever name, huh?).

One of the reasons I love Less Accounting’s messaging is because it’s honest about bookkeeping. It doesn’t try to make bookkeeping sexy (which it isn’t) or fun (which it definitely isn’t). Instead, Less Accounting emphasizes the ease of use of its software, and tries to be authentic and upfront about bookkeeping being something of a chore.

The way Less Accounting’s messaging is positioned makes the opportunity cost of the software (which itself is very low, given Less Accounting’s very reasonable pricing) almost negligible compared to the benefits of using the product. This creates a strong association between the software and solving prospects’ problem, virtually eliminating the opportunity cost objection altogether. The learning resources made available by Less Accounting further strengthens this relationship, lowering the perceived opportunity cost even further.

Principle 2: Rational People Think at the Margin

For our second example, let’s ignore the hilarious notion that economists assume that most people are rational, and accept the principle that rational people think at the margin.

The margin – where rational people think.

Essentially, this means that consumers will choose the product or service that meets their needs in the most optimal way possible, balancing price, opportunity cost, and perceived benefits in each and every transaction. To do this, your prospects need as much information as they can get in order to make an informed (and therefore rational) decision. So what do you do?

Spell It Out

Older, larger companies – especially in the tech industry – are often guilty of trading on little more than their name. This is why the startup ecosystem has transformed so many industries, because the focus has shifted from established, legacy household names like IBM to tiny, scrappy unknown startups that offer genuinely innovative and useful products.

However, if smaller companies with newer products want to play in the big kids’ sandbox and actually succeed, they have to make what they offer and why it’s a great idea almost painfully obvious to prospective customers. In economic terms, it’s vital to make it clear that the marginal benefit of taking action outweighs the marginal cost.

Case Study: Airbnb

Vacation rental service Airbnb perfectly exemplifies the principle of convincing people to take action by appealing to their rationality.

If you look at the hospitality industry as a whole, it’s easy to see why Airbnb has made such an impact. Although many people want to see the world and travel, finding suitably priced accommodation is often a challenge to all but the independently wealthy. Even if cost isn’t a problem, somehow, most hotels feel the same – there’s very little to differentiate one Marriott from another, no matter where in the world you happen to be.

Airbnb changed all that by making accommodation personal. Not only does Airbnb’s messaging emphasize the excitement of discovering new places, it also makes the entire experience very welcoming – note the choice of phrasing throughout the site’s copy.

This appeals to the rational decision-making part of prospective travelers’ minds. If you’re going to spend $200 per night to stay in yet another Marriott in Paris, why not stay at Arthur’s place? It creates a personal connection between guest and host, something that is often sorely lacking from even high-end hotel experiences. The prices are very similar, but the marginal benefits of using Airbnb are substantial, making the service a compelling alternative in a highly competitive marketplace.

Airbnb’s marketing also places great emphasis on the “insider exclusivity” element of its service. Sure, you could ask the concierge of your hotel where to go for the best coq au vin in the city, but I’ll bet Arthur knows more than a few places that serve great food that you won’t find in any guidebook.

I’d much rather stay here than a bland, generic hotel room.

Simply put, Airbnb leverages the principle of economic rational decision making by offering an entirely new travel experience for a similar price. Why simply stay in a hotel when you can live somewhere exotic, if only for a short while, for the same price?

Principle 3: People Respond to Incentives

Some of Mankiw’s principles of economics aren’t as relevant to marketers (such as the concepts that trade can make everyone better off or that governments can improvement market outcomes), but the idea that people respond to incentives is just about as relevant to marketing as it possibly could be.

In economic terms, incentive refers to market forces that affect the price of goods. For example, when the price of a product rises, consumers are often dissuaded from buying it. However, in marketing terms, incentive has more to do with overcoming consumers’ choice between service providers in a competitive market.

Defining the Value of Incentives

If you want to leverage the principle that people respond to incentives, you need to understand what your prospects consider valuable.

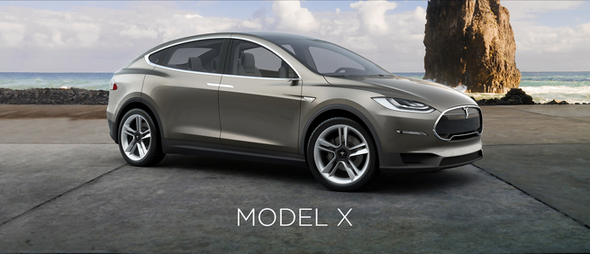

The promise of discounts or other financial motivators is the most common form of incentive. However, depending on your product and ideal customer, this may not be as persuasive as you might hope. If you run a Tesla Motors dealership, for example, the promise of a few hundred dollars off the price of a brand-new Tesla Model X (some models of which cost almost $80,000) is unlikely to persuade anybody – especially when many Tesla buyers are already eligible for up to $7,500 in federal tax credits.

Image © Tesla Motors

So what can you do? First, understand what motivates your ideal customer.

Discover What Drives Your Prospects

Before you can offer incentives that will persuade your prospective customers, you need to understand what motivates them. We’ve talked about understanding user intent before, but you may need to expand your horizons from PPC data if you want to truly “get” what your customers want.

Beginning with demographic data is a good start. Identifying your ideal customers’ age, marital status, level of education, and estimated annual income can yield tremendous insight into what incentives your prospects will find appealing.

For example, a single parent earning less than $30,000 per year will likely find financial incentives more motivating than a retired couple with an investment portfolio and several properties. That’s not to say that wealthier people don’t respond to financial incentives – after all, you don’t accumulate wealth by spending frivolously – but simply offering your product at a reduced price may not be as compelling as you might hope. Sometimes, people want other things.

Case Study: Warby Parker

Eyeglass retailer Warby Parker is an excellent example of understanding the true motivations of your customers and leveraging that knowledge to offer genuinely compelling incentives.

There is certainly no shortage of eyeglass retailers online. However, Warby Parker cleverly combines its unique selling proposition with incentives that appeal to its ideal customer to create a win-win retail experience.

Warby Parker operates a “buy one, give one” program. For every pair of eyeglasses bought, Warby Parker donates a pair to someone in need elsewhere in the world. Many of the recipients of these glasses live in developing countries, in which prescription eyewear is often a luxury. Lack of access to eyeglasses has a serious economic and educational impact, making it one of the most urgent – yet frequently overlooked – problems in developing countries.

Warby Parker’s site offers some interesting information about the program, but that’s not what makes it such an inspired marketing strategy – it’s how this program appeals to Warby Parker’s target demographic.

Warby Parker’s spectacles are effortlessly stylish (full disclaimer – I’ve worn Warby Parkers for years), making them appealing to younger people who want to make a fashion statement with their glasses. Younger people (I’m loathe to use the term “Millennials,” but I suppose I’ll have to for the sake of this example) tend to be more altruistic than older consumers, as several studies have shown, which makes the buy-one-give-one program particularly appealing. Look good, feel good. Who wouldn’t want that?

As a marketing case study, it’s pretty damned close to genius. Warby Parker grew 500% in its first year and surpassed its first year’s annual sales goals in just three weeks, all using word-of-mouth marketing. Warby Parker accomplished this by knowing their ideal customer and offering a powerful incentive that goes beyond the personal and appeals to their customers’ desire to effect real change in the world.

Knowledge is Power

Hopefully, these examples have given you something to think about in your own marketing campaigns. Are you offering incentives that genuinely appeal to your customers? Why should they choose you over a competitor? Does your positioning and messaging “speak” to your prospects? These are all questions worth asking before launching a new campaign.

Of course, if you have questions of your own, be sure to leave them in the comments!

Comments

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.