Product marketing is the process of bringing a product to market. Easy enough right? Well, no. People are picky, competition is fierce, and markets are saturated. Even the best of brands have to work at this.

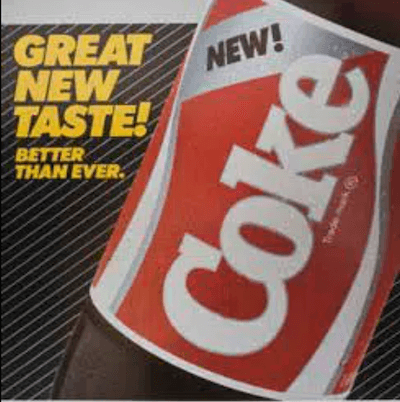

Exhibit A: Coca Cola’s New Coke

New Coke wasn’t just a marketing fail, it actually resulted in protests.

But the best way to learn is to learn from the best—the good and the bad. So in today’s post, we’re going to walk through:

- 10 product marketing examples from top brands like Apple, 3M, Clairol, and more.

- Why they worked (or why they didn’t).

- Takeaways you can apply to your own product marketing strategy.

Let’s get started.

Product marketing examples: The good

You don’t have to be a big brand with a big budget to apply the tips and takeaways from these great product marketing examples. Read on and get inspired!

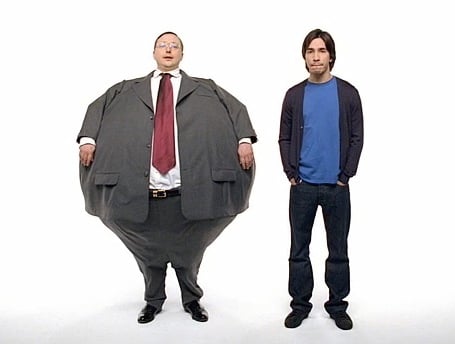

1. Apple’s Mac vs PC campaign

You can’t have a product marketing conversation without mentioning Apple. Namely, its Effie Award-winning Mac vs PC marketing campaign where PC (the suit-and-tie-wearing office guy) is always struggling to keep up with Mac (the cool, hipster guy).

Bloated with malware.

There are 66 different (and very funny) iterations of the ad, but the same features are mentioned in every video: iMovie, iTunes, iPhoto, and ease of use. It’s clear that Apple was speaking to people looking for a computer that could support personal and creative needs.

The takeaway: Don’t just sell your value proposition, communicate what your audience cares about. Even a brand as massive as Apple pinpoints its messaging in each campaign to speak to the personas it’s targeting.

2. SoFi: Don’t sell your product; sell emotions

Many product marketers fall into the trap of “selling the product, not the experience.” No one wants your product. No one wants any product. They want a solution to their problem. They want to feel relieved. Excited. Confident. Secure. Safe.

You see, talking only about the benefits, features, and facts and you only engage two areas of the brain—the two that simply decode words into meaning. Incorporate emotional words and images in there and the game changes.

Take SoFi. Is it selling personal loans in the ad below? Nope. It’s selling the feelings of empowerment (“kick unnecessary fees out”) and dance-worthy joy over saving money.

The takeaway: Emotional marketing doesn’t have to mean sob-worthy Subaru stories. Just use interesting words and expressive imagery to represent how your customer will feel as a result of your product.

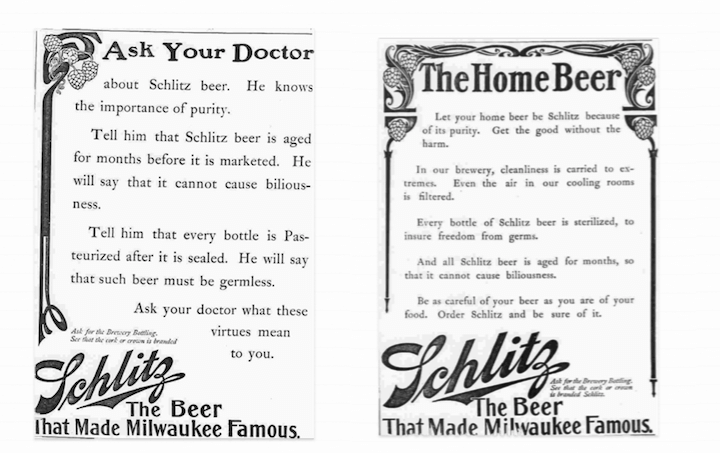

3. Schlitz: Tell them how it’s made

In the early 1900s, Milwaukee brewer Schlitz was struggling. It ranked eighth among American brewers and had little hope for growth. Every brewer at the time screamed about their beer’s “purity,” but with no clarification of what “pure” meant, no brewer could top the other.

They eventually hired Claude Hopkins (now one of the fathers of modern advertising), who requested a tour of the brewery. After seeing plate-glass rooms that dripped beer over pipes, twice-daily cleaned pumps, four-time sterilized bottles, and 4,000-foot deep artesian wells, he had only one question: ”Why in the heck don’t you tell your market you do this?”

It was because every brewer followed this protocol, but Hopkins strongly advised Schlitz to advertise stories about this because no other brewer did, and these would clarify “pure” for consumers.

So Hopkins created ads like these:

They went from eighth to number one in American beer in just a few months.

The takeaway: Don’t just write product descriptions—tell true stories that involve your potential customers, take them behind the scenes, and elicit emotions.

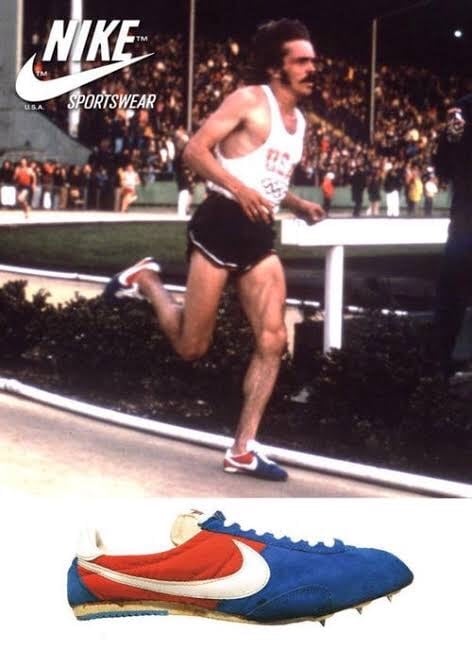

4. Nike: Do what your competitors won’t do

In the 1970s and 80s, when Nike tried to break into the casual shoe market, it fell behind Reebok.

It then used a then-unknown, and sometimes scoffed at, marketing tactic: celebrity endorsements. Nike’s first celebrity athlete endorsements started in the 1970s with tennis player Ilie Nastase and track star Steve Prefontaine, catapulting its revenue to $270 million. By 1990, after getting Michael Jordan on board, its revenue hit $2.2 billion. Today Reebok is about 1/45 the size of Nike.

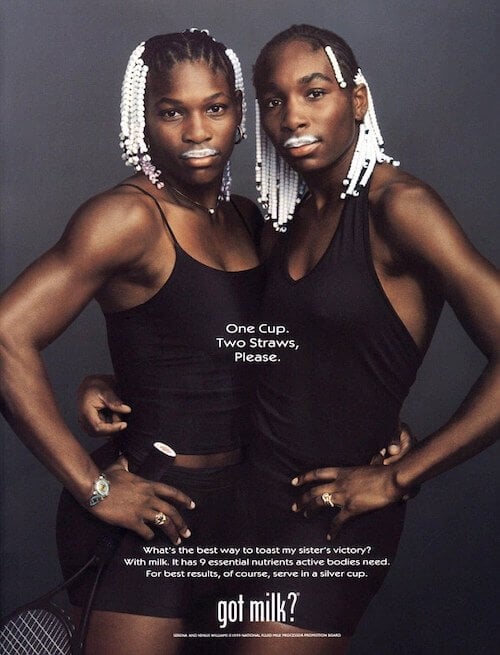

In the early 1990s, Pepsi and Coke dominated the beverage market, spending more than $100 million to advertise just one of their varieties. At the same time, boring old milk consumption was on the decline in California—not good for dairy farmers.

The National Dairy Board and California Advisory Board had to try something with their minuscule $23 million advertising budget. The hired ad agency Goodby, Silverstein and Partners (GS&P) hypothesized that advertising to milk drinkers, rather than non-milk drinkers, might be the ticket. Through focus groups, they found consumers only drink milk with something else. Also, they never think about it until they run out of it.

So that led to the creation of the first “Got Milk?” commercial:

National milk sales went from being in decline to increasing 7% in California by 1994. And though intended just for Californians, it became a cultural phenomenon. The campaign garnered three Gold Clios and remains one of the greatest marketing campaigns to this day.

The takeaway: You don’t necessarily need to find a new audience to increase product sales. You can move the needle by increasing demand even among your loyal fans.

📗 Free Guide >> The 30 Best Ways to Promote Your Business

6. The 4-Hour Workweek: Make a promise you can actually deliver on

Remember the Ab Rocket? The Rock-N-Go Exerciser? Or any of the other ab rockers out there? These products, which sold for $100-200, were called out by Consumer Reports in 2009 as being the same or less effective than zero-equipment ab workouts.

Making a promise you can’t deliver on means you’ll only survive until your market figures that out, and with online reviews as powerful as ever, this is not long at all. You don’t have to come through on your exact promise; you just need to deliver value.

For example, Tim Ferris’ “4-Hour Work Week” sounds unbelievable. But the content of the book doesn’t boil your work week down to just four hours. However, it does give you a plan for “escaping the 9-5 workday, living anywhere, and joining the new rich.”

And Tim’s market finds that pretty cool.

The takeaway: Product marketers have to make promises to get people excited about trying new things. But if your promise is a lie, you’ll be in trouble.

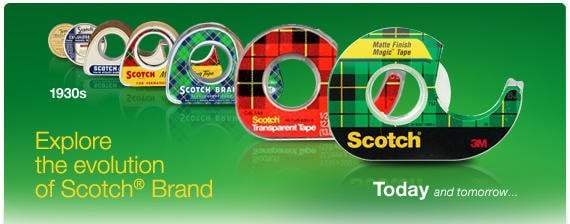

7. 3M: Have a culture of innovation

When you think about innovation, you probably think about touch screen gadgets and fancy platforms—not Scotch tape and Post-It Notes.

But 3M is now a $114 billion company with over 100,000 patents—thanks to a culture of innovation. What does that look like? In this i4cp interview, Jon Ruppel, 3M’s then-VP of Global HR Business Operations said ”We automatically share our discoveries and technologies across the company. No one business owns a particular technology and it’s natural to work across business lines in support of the broader 3M goal.”

He said the company also:

- Listens to any new product idea, regardless of the employee or their position or the seeming absurdity of their idea.

- Gives each employee 15% free time to explore new ideas.

- Keeps a diverse workforce regarding thinking, culture, gender, ethnicity, and experience.

- Embraces failure. Employees do not get fired for failed product launches. They are celebrated.

Wow.

The takeaway: Innovation requires failure! And though it can’t be taught, it can be rewarded and harnessed in your company’s culture to build patent-worthy products.

Product marketing examples: the bad

The best way to learn is to learn by mistakes. Correction: to learn by others’ mistakes. Right?

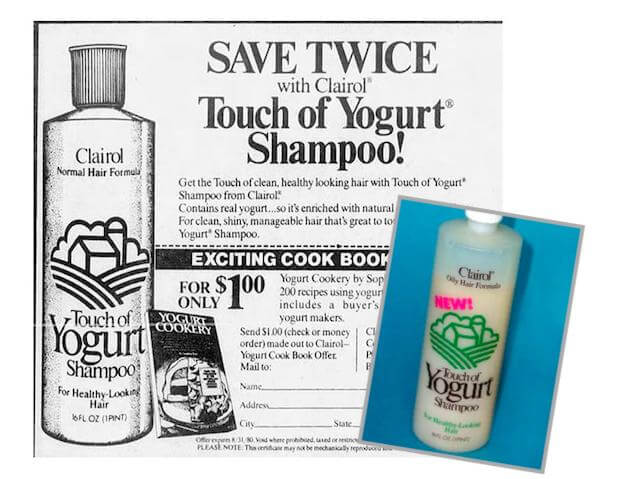

8. Clairol: Don’t be afraid to fail

Another example is Clairol. While its provocative Herbal Essences shampoo ads have enjoyed massive success, its 1979 “Touch of Yogurt” shampoo bombed in an epic way.

Mmm…hairy yogurt anyone? Some confused customers even ate it and got sick! To cap it off, the real yogurt in the shampoo actually went sour. And reeked. How about you cap that off with a multi-million-dollar class-action lawsuit while you’re at it…

But is Clairol still a top brand in the shampoo and hair coloring industry? You bet.

Take away: Don’t be afraid to fail. The most successful businesses out there didn’t get it on their first try. In fact, it’s often the failures that built up to their success. Experiment, learn, and power on.

9. McDonalds: Know your audience

Finally, McDonald’s took a big swing and a miss with the Arch Deluxe. At the time, McDonald’s was known mostly as a restaurant for kids, so they tried the Arch Deluxe to target adults.

Have you ever thought about fine dining downtown…and had McDonald’s pop into your mind? Their market didn’t either. Guess they weren’t “lovin’ it.”

McDonald’s dropped $300 million on the research, production, and marketing of the Arch Deluxe, “the burger with the grown-up taste.” And it’s now one of the biggest product flops in history. But strangely enough, you can still get it in France and Russia.

The takeaway: Consider your core audience carefully before you launch and promote a product that might (really) not resonate.

10. Lifesavers: Create new brands for new products

It’s always good to think outside the box and test new ideas and markets, but this can be hit or miss—sometimes a catastrophic miss. For example, Life Savers once marketed soda in the 1980s.

It actually did well in taste tests, but once sold nationally, it tanked. It turns out, consumers thought they’d be drinking liquid candy. Sounds delicious to me, but the market as a whole didn’t like the idea.

Now let’s take a look at Procter & Gamble—the same company that makes diapers also makes razors. And 63 other product lines, including Bounty, Crest, Dawn, GIllette, Olay, and the list goes on.

The takeaway: If you want to branch out with a new product or to a new market, you might try creating a completely new brand. You won’t have the built-in name recognition. But you’ll overcome the barrier that causes your market to think you can’t possibly do different products well. (If you do this, make sure to build a solid go-to-market strategy!)

11. The Segway: Ensure product-market fit

If you build it, they will come. Kinda. Sorta. Well…not really.

Let’s take the Segway: Code-named “Ginger,” rumored to become an alternative to the automobile, predicted to sell 10,000 units a week, and priced at $5,000.

The reality? It horrified consumers and investors, sold 38 units a week, and is used mainly only by police departments, tour guides, and warehouses (at least it has a market, right?).

Image source

Image source

The takeaway: As awesome as your product sounds, always do your product-market fit homework and make sure there’s a market for it!

Takeaways from these product marketing examples

Doing anything outside the norm terrifies most companies. What if it results in failure? What happens then? But product companies that take risks not only recover, they often become enduring cultural icons. And it’s due in large part to their willingness to integrate these secrets into their operations. Which of the lessons from these product marketing examples inspires you most?

- Communicate what they care about

- Don’t sell your product; sell emotions

- Let customers in on how it’s made

- Do what your competitors won’t

- Market to your existing customers

- New product? Try a new brand name

- Make a promise you can actually deliver on

- Have a culture of innovation

- Don’t be afraid to fail

- Know your audience

- Ensure product-market fit

About the author

As a freelance copywriter, Dan Stelter crafts persuasive lead-generating content for B2B software, SaaS, and service companies, earning him the moniker “The B2B Lead Gen Guy.” When you don’t find Dan helping B2Bs swipe more market share from competitors, you will find him reliving the good ol’ days of The Simpsons.