“Writers are all broke.”

“It’s a vocation. Not really a career.”

“Writing can be fun. But not lucrative.”

That’s all B.S.

Writing is not fun. It’s a daily slog. Sometimes, it’s not terrible. But mostly it’s incredibly difficult. Requiring 100% attention and focus and energy.

And it can be lucrative. But only if you do it right.

Want to be a freelance writer? Here are seven no B.S. tips for how to find and keep freelance writing jobs (from an accidental writer who’s made a lot of money doing it).

1. First, Get the Money

Content isn’t king. Cash flow is.

Your ability doesn’t matter if the lights don’t stay on.

Your primary problem in the early days of freelance writing is obscurity. So you get work where work commonly comes from: job boards.

A never-ending supply of freelance writing gigs are readily available. Relatively low-hanging fruit to pluck off the nearest branches as it ripens.

But here’s the thing.

If you ever want to get off the job board hamster wheel, you gotta ditch them ASAP. (This includes writing sweatshops like iWriter, Upwork, Craigslist, or god forbid, Fiverr.)

Yes, this is a real subway ad for Fiverr. Who says wage slavery can’t be glamorous?

Not that you can’t ever refer to them in the future. But you can’t expect their work to sustain you over the long haul. Here’s why.

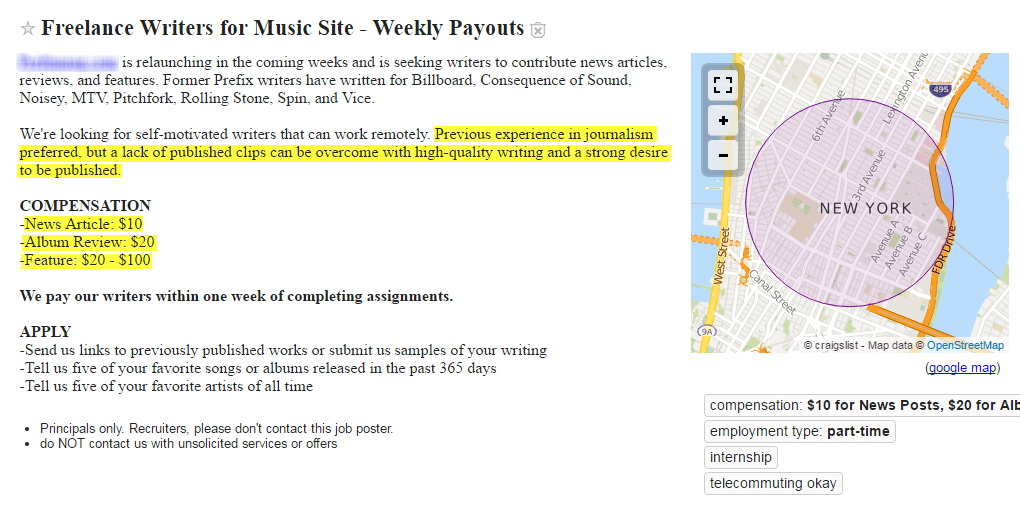

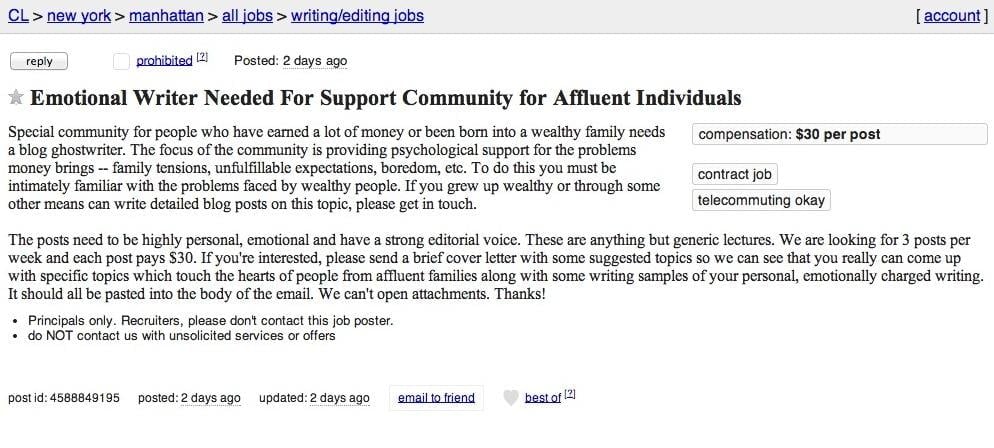

Problem #1: Job boards are filled with mostly low-price, commoditized freelance work.

Job boards are like cattle calls. A bunch of generic postings looking for generic work from generic writers. Therefore, they’re only willing to pay generic amounts.

LOL

You gotta eat. So get ‘em if you need ‘em. But over time, if you do the next few tips properly, the work and clients from those job boards will only serve as an albatross (<— geeky metaphor only appropriate for writers).

Problem #2: Zero control over scope.

Job board postings commonly list the work they’re looking for. Put together by someone who most likely has little-to-no experience in the actual thing they’re hiring for.

That presents a few issues.

LOL

Most commonly, the scope is all over the place. It’s unreasonable. Timelines are literally impossible. And of course, the rate for this mess is a hilarious joke.

But sales is positioning. You come at them from a job board and your chances of negotiating said terms are slim to none.

Whereas if you come through an inbound request or personal referral, you’re now seen as an expert.

Which is critical to making the paid freelance writing leap.

2. Recognize the Difference Between Good and Bad Work

Some work pays the bills. That’s the stuff you need in the beginning.

Other work provides attention. That’s the stuff you need to go “next level.”

The hard part is knowing when to take on each kind. It’s a literal Catch-22. You gotta balance the junk without neglecting the “brand building” stuff (that we’ll revisit in a second).

Tip too far one way or the other and you’re in trouble.

Thankfully, at some point, if you do it right, they merge. So the good work also pays the bills.

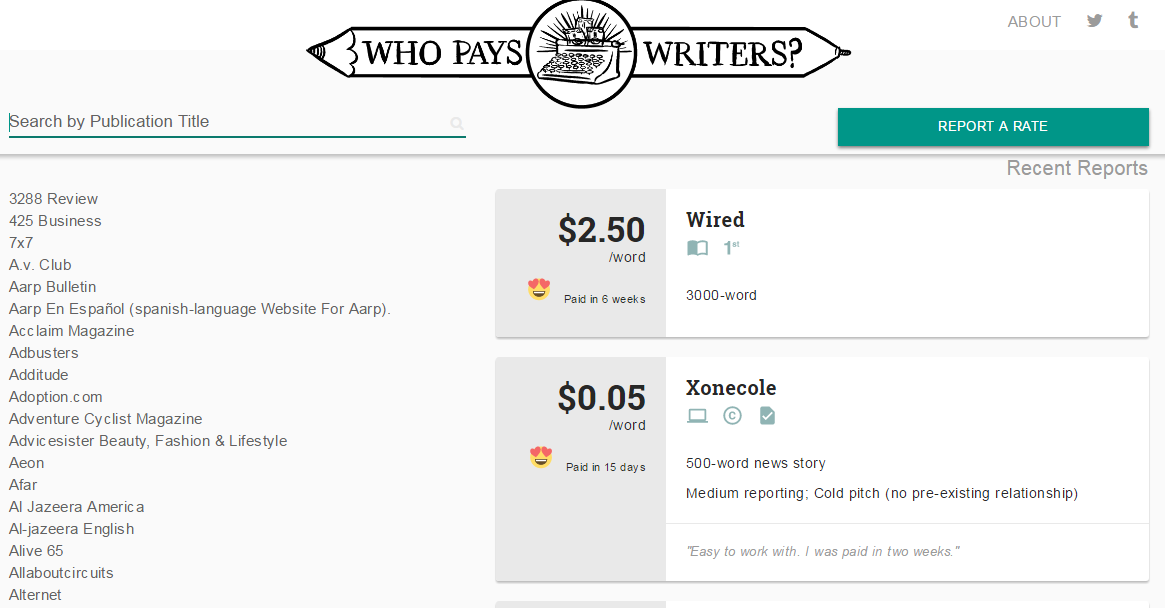

whopayswriters.com is a great resource for finding a publication’s rates

Your teachers in grade school were wrong after all. There is such a thing as a bad question. And a bad client. And a bad project. And too much life-sucking work will kill your ambition. It will slaughter your future potential profitability. And it will consume any free time you might have to go after the bigger assignments.

Fortunately for us who skew towards words, freelance math is stupidly simple. There are two ways to make more money:

- Charge more.

- Write more.

That’s it. No tricks or hacks. At some point, you’ll hit a ceiling on #2. You should always try to increase that capacity. But you’ll inevitably tap out at some point after a few thousand words or four to six hours per day.

Instead, most writers (and freelancers in general) should (but don’t) improve #1. First.

LOOOOOOOL

Let’s go back to job boards. Completely relying on them forever is a death sentence. But browsing them from time to time is perfectly acceptable. If you know what you’re looking for.

Every once in a while, a job board post will leap off the page. Because it’s the rare exception that ticks all of your self-imposed boxes.

Then sales becomes easy. It’s straightforward. No BS-closing techniques required.

- I’m a perfect fit for what you’re looking for.

- Here’s my work that illustrates this.

- Hope to talk soon.

There is one critical sales skill, however, that you’ll need to master.

Your pipeline.

Sales is a numbers game. So treat it like such.

- Reverse engineer what success looks like. Let’s say you wanna make $10,000 a month. Cool.

- Each client is worth $1,000. (Let’s keep the math simple.)

- So that means you need 10 clients over the next few months. Again, keeping the math simple, let’s say you just want to add one new client each month.

- Unfortunately, one lead does not equal one client. Ten do. Sometimes, 30 do.

- Break that down into simple, weekly and daily activities. 30 contacts divided by 30 days equal one new person each day.

- So what are you doing, today, right now, to reach that one new person?

Don’t get hung up on the tactics or mechanics. Use carrier pigeon if you have to. Just talk to people.

3. Specialize ASAP

Most of my early writing was a humble attempt to bring attention to myself and my business. To generate paying clients for various marketing services.

Because you can’t make any money actually writing… right?

My first paid writing gig was for $0.06 a word. I had no idea what I was doing. Had no idea what pricing per word yielded.

(In case you’re wondering, I don’t even think that came out to minimum wage.)

So, no. You can’t live off that.

But less than nine months later, I was charging $0.30+/word and pulling in over six figures annualized.

Part-time.

While running another company with employees, clients, and all the headache that comes with it. And also having a family with beautiful kids, wife, and pug. (The pug’s the neediest one.)

So, yeah. You can make money writing. You just need to figure out where you excel. And then exploit the hell out of it.

See, that “nine month” timeline is disingenuous. Yes, it’s accurate. (And since that point, revenue has nearly doubled.)

But it doesn’t take into account all of the stuff it takes to get someone to this point of opportunity.

I can write. Very well. In an extremely limited scenario. (Emphasis on extreme.)

I cheat. I have almost a decade of hands-on subject matter experience. I studied it in school. Was even a good student. Got an MBA. (With the debt to prove it.)

Then I got a few jobs. In-house at various places. Implementing and learning and iterating on a daily basis. Then I left to start my own business. Then hired employees. Had to figure out how to manage, scale, sell, budget, etc.

Point is there’s an intersection.

When you combine writing with something that you’re generally interested in and already good at, you win.

This requires an insanely high degree of self-awareness. (A levelheaded criticalness that doesn’t devolve into the self-loathing common with writers.)

Pretty much, yeah.

Almost everything you do should be specialized in some way.

- The clients you work with.

- The types of sites you want to write for.

- The actual writing you do.

- Etc.

I can’t write fiction. The New Yorker would laugh in my face. Never wrote for a single “real” magazine. Book-length scares the hell out of me. And I feel like the biggest fraud and hack in the world when I send these articles to someone who can actually write and has actually been published in The New Yorker.

But I can write a blog article. A few thousand words, in a sarcastic, pithy way. For people who’re OK if there’s a few inappropriate jokes.

And that’s about it. I suck at everything else. Which rules out like 99.9% of people and clients who might like what I do (and be willing to pay for it).

Case in point: The first time a new client read an eBook I submitted, she replied, “This reads like an article.”

Well, yeah.

4. Find a Market that Already Exists

A good close rate in sales is like ~25%.

Yours should be closer to 75%+.

Not because you’re great at sales. But because you’ve found out where that specialization works best. (Or the unicorn-esque “product + fit” that tech wantraprenuers rave about.)

Here’s the trick.

You can’t invent the market. It either exists, or it doesn’t.

Beware of people and companies who want to “create a market” for their product or service. The lack of competition is an ominous, dangerous sign.

How to nail market specialization as a freelance writer in one easy step.

Jobs didn’t create the first computer. Musk didn’t invent the first electric car. Same applies to Sergey + Brin and Zuckerberg.

In each case, these legendary entrepreneurs, whose companies are among the most innovative and popular and profitable, didn’t invent the market. They just exploited it. Perfected it.

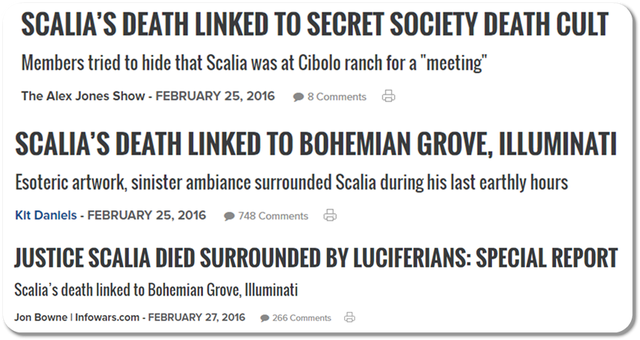

Look for “echo chambers” online. Echo chambers are actually big markets!

Huh.

Tech is one. Social media another. Design yet another. WordPress. Gluten-free. Travel. These are all off the top of my head. A little digging would reveal hundreds more.

Then you’ve got different formats. Blogs, magazines, video, podcasting, whatever.

So…which combination of those variables is (a) willing to pay a decent amount and (b) aligns with your specialty?

Find it and your freelance writing life becomes exponentially, magically easier.

Two ways to tell if you’re on the right path:

- Unexpected, inbound writing requests start coming in, and

- Client retention is 80-90%+

5. Prioritize Recurring Revenue

Project-based freelancing work is often unprofitable.

Here’s why.

❌ Project work tends to come in batches. I don’t know why. Blame the freelancing gods. But it’s feast and famine. One month you’re slammed. And the next you’re completely dry.

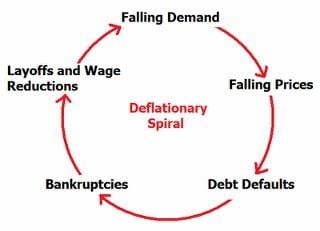

❌ You don’t charge enough. So a new project might “pay the bills.” For one week or one month. Maybe. But there’s no profit left over afterwards. So you’re treading water. Literally going in circles.

❌ You don’t have the extra resources (read: time, money, and energy) to do the longer-term, brand building stuff that’s gonna get you future work.

So what’s the solution?

Deflationary economics. Well not really. But the response to deflationary economics.

Here’s what I mean:

Think about how technology drives down the price of goods and services. SaaS for example. Netflix. Spotify. Hell – custom websites (see: Themeforest, 99Designs, etc.).

Recurring revenue is the freelance writer’s silver bullet. Without it, you’re left schlepping for scraps every ~45 days, like clockwork. And good luck trying to pay a mortgage, feed your family, or hire employees.

Pursue recurring revenue at all costs. Even if the per-unit cost ends up being a little less.

Me too!

Now, you’re not Netflix. Writing as a subscription service isn’t a “thing.” Although it is a good idea, there isn’t yet (to my knowledge) a viable, paying, lucrative market out there for it.

The alternative? Consumables. Think razor blades.

An article, for example. Generally, the people who buy articles want to (or need to) publish X per month. So there’s built-in demand.

Give them X per month. Ongoing. Even if it costs you a little up-front. Because you’ll make it up over six months+.

Sometimes, the pursuit of recurring revenue requires that you change or alter the service you sell.

Do it. You won’t regret it.

6. Never Stop Testing to Improve Value

Most people can’t write. That’s not an understatement. Go read your emails from friends and colleagues to affirm.

LOL

It’s a skill. A service. That’s intangible. Like thin air.

Ever try to write something for someone who can’t write themselves? How’d that work out for you?

A bloody nightmare, most likely. And that’s why those people don’t pay writers well. Because they can’t tell the value of one over the other.

For example, let’s get quotes for a new website redesign. One might quote you $1,000. Another $10,000. And yet another $100,000.

So what’s the difference? How does the person footing the bill make a decision?

If they’re smart (and that’s a big IF with some clients), they pick the solution that will make them more money in return…even if it costs them a little more upfront.

The good clients understand this. And you only want to work with good clients. (See tips one and two above.)

So you need to figure out what “value” is to them. If it’s a website, maybe it means you’ll increase their conversions. So sell the value of those new leads.

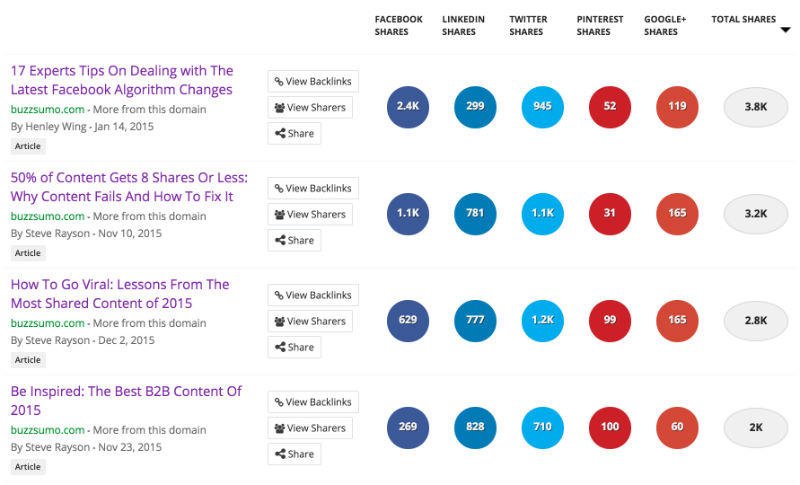

The “value” of writing can be subjective. But not always.

The first thing that comes to mind is readership. The dreaded pageview. But social shares also work. The editorial, organic links or referrals back to a post.

Generally speaking, the more attention and eyeballs your writing gets, the higher you’re gonna get paid. It’s not always fair, but it’s true.

So test. In every piece. A new iteration. A new promotional method. A new format or style. Add more images. Write better headlines. Etc. Etc.

Is Kanye West the best musician? Probably not. (He’s not even a great human being.) But he sells records and sells out arenas.

7. Writing is a Craft. So Treat It As Such.

Fitzgerald was 1,000,000 times the writer most of us can aspire to be.

Yet he was broke most of his life. Pitching magazine articles instead of focusing on his specialty: novels. And then he drank himself to death by the age of 45.

One stereotype is that artists are creative. The other is that they’re also commonly starving or suffering. Their work is the product of some divine intervention. It comes and it goes.

Yes and no.

The key word in the title of this article isn’t “writer” but “freelance.”

It means you need to approach writing like a cold-blooded professional. You need to eat. Which means you need to hunt.

Christopher Walken discovers the joy of freelancing

Acclaimed food writer Michael Ruhlman calls cooking a “craft.” He refers to most chefs as craftsmen (as opposed to “artists”). The difference lies in the pursuit of said vocation. Crafts require discipline, and mind-numbing repetition.

So don’t break the chain. Confront resistance head-on. Every single day.

There’s a whiteboard in my office. Each month, I write out my writing revenue goals, broken down into weekly and daily targets. That means if one day is slower, I have to make up for it by the end of the week.

I want to increase that number each month. Which means I need to become more efficient in my process (batching research, compiling statistics and images, etc.). Self-imposed timelines need to be tight (only allowing ~3-4 hours per article after prep work so I don’t overthink and overanalyze stuff). My own writing needs to improve so edits and client feedback reduce (and/or go away entirely).

In short, every single aspect needs to improve. Constantly.

So admit it: you suck. In some areas.

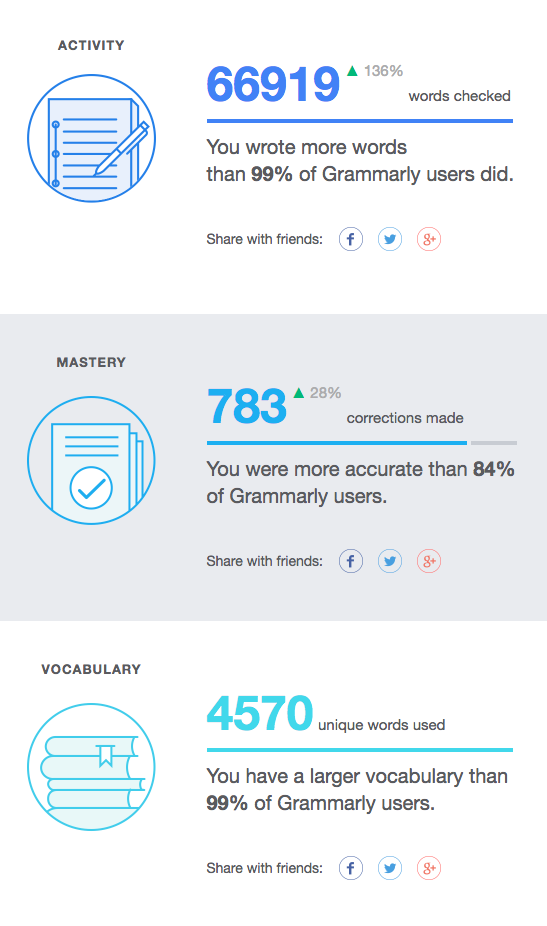

I suck in lots of them. For example, I’ve probably already made a few punctuation errors here. My process now calls for each article to be run through Grammarly to slowly but surely weed out those bad habits.

Then Grammarly sends a weekly progress report to tell you how you’re doing. They calculate your words written, corrections made, and vocabulary used over the course of a week. Then they compare the results against (1) your own past results and (2) all of Grammarly’s customers.

Not a bad week. But still a long way to go. One day at a time.

Do the Work

I like to run. But I’ll never, ever qualify for the Boston Marathon.

There are a few legit excuses. Don’t have the right genetic build, VO2 max, or whatever other innate “gifts” people like to blame. There’s science behind these.

But the simple, honest truth?

I don’t run enough.

Pass.

Runnersworld partnered with Strava to analyze “7,164 marathoners who ran a Boston qualifying time versus 24,330 marathoners who didn’t qualify” during a twelve-week training marathon training cycle.

The found that Boston qualifying runners ran almost twice as much (560 miles compared with 300) and also ran almost two more days per week.

Want to get freelance writing jobs? Become a better writer. By writing more.

Want more job advice?

Check out these recent articles:

Comments

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.